Early Automobile Racing

Story written by Andrew Capets for the Trafford Historical Society, May 2016

The Pittsburgh Magazine has a regular article written each month by the beloved filmmaker and producer, Rick Sebak, entitled All Roads Lead To Pittsburgh. It’s intriguing to read about the noteworthy people in history that either passed through the city, had an influence on advancing the city, or how the city itself had an impact on those individuals. Researching the local history of Trafford, I think about the people who came through this town and how they themselves made contributions to history. I occasionally come across stories of residents who were lucky enough to rub elbow with famous people.

I was asked to look into the topic of early automobile racing in Trafford. While Trafford was by no means an epicenter of professional auto racing, there were a few residents of the town that spent a good part of their lives pursuing this thrilling, yet dangerous pastime. They even rubbed elbows with a few famous people along the way.

From my own family history, I dug into the story of my great grandfather Roy C. Bigler, who pursued auto racing as a hobby and was successful in winning a few amateur races in Western Pennsylvania. Notably, he took first place in the 1914 Summit Mountain Hill Climb in Fayette County. The race started at the bottom of the hill in Hopwood and the drivers raced to the finish line near the Summit Hotel. Bigler set the bar high for the professional racers with the fastest time up the hill earning him the sought-after “Loving Cup.” Bigler was a successful contractor in those days. One of his contracts was to build a steel-beam bridge in Trafford across Brush Creek at Mahaffey Hill. He also built the Irwin Waterworks reservoir on Pennsylvania Ave in Irwin.

My third great-uncle, Edward J Blend Sr., teamed up with Roy Bigler as his auto riding mechanic. They rode in a 1911 Mercer Raceabout competing in various racing venues in the tri-state area. On one particular weekend, Bigler, then known by the racing nickname “Reckless Dan Rex,” placed first in the Waynesburg County Fair. The next day they travelled to Clarksburg, WV and won the Jackson 10 Mile Sweepstake.

My third great-uncle, Edward J Blend Sr., teamed up with Roy Bigler as his auto riding mechanic. They rode in a 1911 Mercer Raceabout competing in various racing venues in the tri-state area. On one particular weekend, Bigler, then known by the racing nickname “Reckless Dan Rex,” placed first in the Waynesburg County Fair. The next day they travelled to Clarksburg, WV and won the Jackson 10 Mile Sweepstake.

Winning these events would have certainly drawn the attention of the professional racers in attendance on the day of the event. Family lore tells of Bigler and Blend befriending famed racing legend Barney Oldfield. Oldfield was considered a pioneer in early auto racing during that time. Oldfield took 5th place in both the 1914 and 1916 Indianapolis 500, and he was the first person to run a 100 MPH lap at Indy. This photo below taken in Cavittsville in 1915 or 1916 shows Barney Oldfield behind the wheel of Roy Bigler’s Mercer. It’s likely that the Great War brought an end to their racing escapades. After the war, Bigler continued to work as a self-employed contractor, while Blend worked as an auto repairman. In 1922, E.J. Blend registered with the Westmoreland County Prothonotary to open the Trafford Auto Repair Company. He entered into an agreement with the Airland Motor Company of Greensburg to sell Nash cars in Trafford.

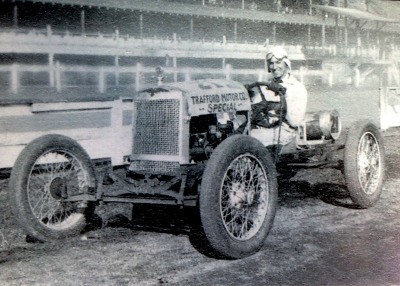

It was about this time that another local family opened an automobile repair business in Trafford. In 1921, Ivan Mikan Sr., then working for the Westinghouse Manufacturing Company, built an auto repair garage on the corner of Seventh and Forest to operate with his sons. By 1924, Ivan Mikan Sr. partnered with Joseph Schneider to form the Trafford Motor Company. Schneider was a sheet metal employee also working for Westinghouse Manufacturing at the time.

During the 1920s, the racing circuit in Western Pennsylvania was drawing large crowds of spectators. Ivan Mikan Jr. was just starting to build his reputation as a challenger on the circuit earning him the nickname “Cy” for his cyclone speed around the track. In 1921 he competed on the Uniontown wooden board track built in Fayette County after the Summit Mountain Hill climb was outlawed. It was at this race that Mikan could have rubbed elbows with the likes of Arthur Chevrolet and Tommy Milton.

During the 1920s, the racing circuit in Western Pennsylvania was drawing large crowds of spectators. Ivan Mikan Jr. was just starting to build his reputation as a challenger on the circuit earning him the nickname “Cy” for his cyclone speed around the track. In 1921 he competed on the Uniontown wooden board track built in Fayette County after the Summit Mountain Hill climb was outlawed. It was at this race that Mikan could have rubbed elbows with the likes of Arthur Chevrolet and Tommy Milton.

In 1925, Mikan raced a 10-mile event in front of a crowd of 15,000 at the Fayette County Fair, taking second place in his Rajo Special. That same year he challenged the competition behind the wheel of a Frontenac. Cy Mikan’s success certainly thrilled racing fans across the area and surely captured the attention of some of the sports’ professionals as well. It’s possible that Mikan first established a friendship with racing legend Tommy Milton at the Uniontown board track. Tommy Milton, the first two-time winner of the Indy 500, probably came to Trafford during those early days of racing as the two racers became very good friends.

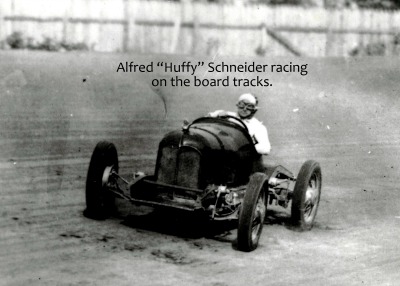

Mikan was not the only Trafford resident to enter the racing circuit in the 1920s. Alfred “Huffy” Schneider, brother of business partner Ivan Mikan Sr. was also running the circuit. Other Trafford contenders included Frank Cipra, Robert McCutcheon, and Earl Cashdollar. In 1926, while Cashdollar was participating in a Memorial Day Race in Monongahela City, his vehicle plunged through the raceway fence. The crash was devastating enough to make spectators question the condition of the driver and the Indiana Gazette reported “Cashdollar of Trafford City was probably fatally injured.” Cashdollar may have been hurt in that wreck, but it did not keep him out of racing. In fact, he participated in another Memorial Day race seven years later in Jennerstown PA. During that race Cashdollar was one of the drivers who “figured in the accident” that caused a crash that took the life of Roy Forest Jones, a 24 year old racecar driver from Johnstown. ‘Huffy’ Schneider was also at that fatal race and placed third in the event. Cashdollar finished the race in fourth place. The racecar drivers in those days accepted the risk of the sport, and this danger clearly brought the spectators back again and again to the packed venues.

In May 1927, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported, “The latest star of the local dirt track fraternity to enter the Butler Gold Cup event is Ivan ‘Cy’ Mikan of Trafford, PA. Mikan, one of the veterans of the game, has had a colorful career on the dirt tracks and is rated one of the most daring drivers in this hazardous sport. He is accorded an almost even chance with William ‘Speed’ Gardner, the favorite, for first honors. Mikan is a great friend of Tommy Milton, former world’s champion, and has set his heart on reaching the goal attained by the Indianapolis race. Cy is working daily on a new speedway creation which will receive its baptism at Butler, and is in consultation with Milton.”

The 1927 Butler race was not won by Mikan that day, but instead went to Marty Klaus of Swissvale. Local papers reported Cy Mikan of Trafford, driving a Frontenac, pressing the winner during the last 50 laps. “Mikan drove his car at breakneck speed and attempted to overcome Klaus’ lead, but at the finish was trailing by half a lap. William ‘Speed’ Gardner, driving a Reo Flying Cloud, finished five laps behind Mikan.”

In those days Cy Mikan was teaching night school at Carnegie Institute of Technology as an instructor of automobile operation and maintenance. It was at Carnegie Tech that he would meet a student in the aeronautical engineering program named John “Jack” Carson. Carson would join Mikan in building a machine with the goal of competing in the Indianapolis 500. Carson and Mikan would have their name on the car, but it was going to take more than just these two men to pull it off.

The Mikan-Carson team surround themselves with other local men who were mechanically skilled to design, build, and test a winning car. Notably, three of these men were William ‘Speed’ Gardner, Reynold Peduzzi Sr, and Steve Ference. Gardner, then employed as a mechanic in the service department of E.S. Carpenter Inc., in Pittsburgh, joined the men at the shop to build the vehicle. He would be one of the team’s drivers. Reynold Peduzzi, brother-in-law to Cy Mikan, was the proprietor of the Reynold Motor Company in East Pittsburgh. Peduzzi was instrumental in providing the team a location to build the car and would have provided a selection of equipment to machine and tool the parts necessary to build parts from scratch. And finally, Steve Ference, a friend and neighbor of the Mikan family. Ference was living on Seventh Street in Trafford and would have been drawn to the activity of the Mikan garage. Ference himself was a skilled mechanic then employed by a Chrysler Plymouth dealership in Pittsburgh.

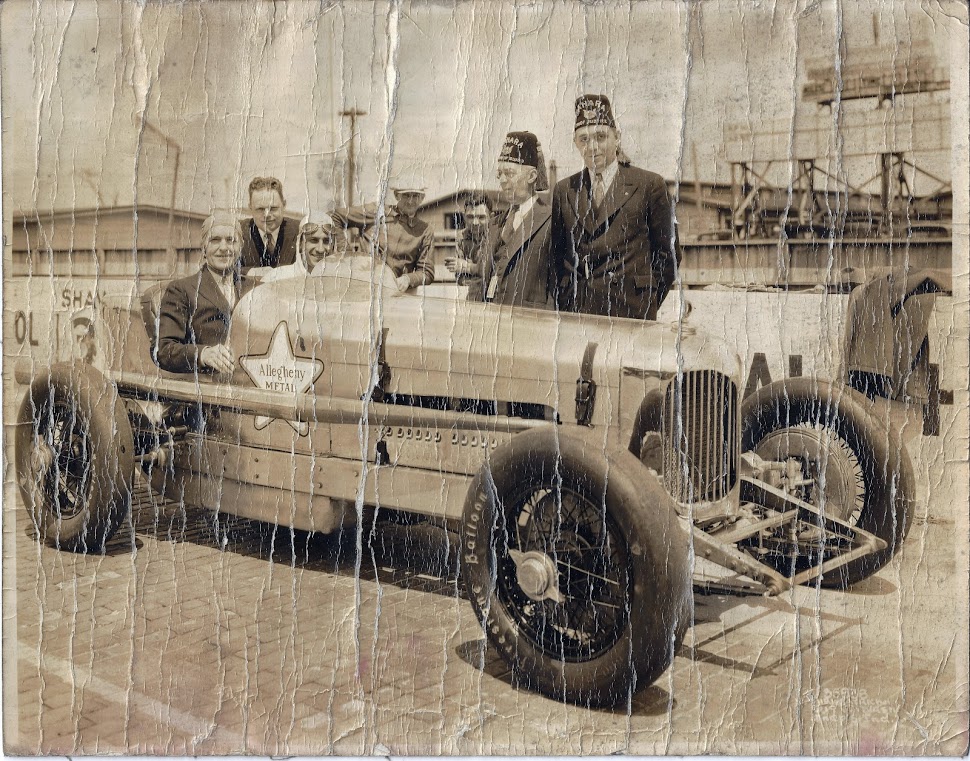

The team started with an eight cylinder Studebaker motor, 337 cubic inch displacement, front wheel drive that would sit on a Duesenberg axle. The body and equipment were constructed from products of the Allegheny Steel Company, and so they called their car the Allegheny Metal Special. They worked through the winter constructing the various parts for the car.

Three months before Cy Mikan would make his first attempt at qualifying for the Indianapolis race, his father Ivan Mikan Sr. would succumb to pneumonia and pass away at Columbia Hospital in Wilkinsburg at the age of 59. In May 1932, the men headed out to Indianapolis to enter the qualifying race. An average speed of at least 100 MPH was needed in the 10 mile qualifier. 72 cars made an attempt to be one of the 40 to run on that Memorial Day. Unfortunately, this was not going to be the year for the Allegheny Metal Special and the team returned to Pennsylvania.

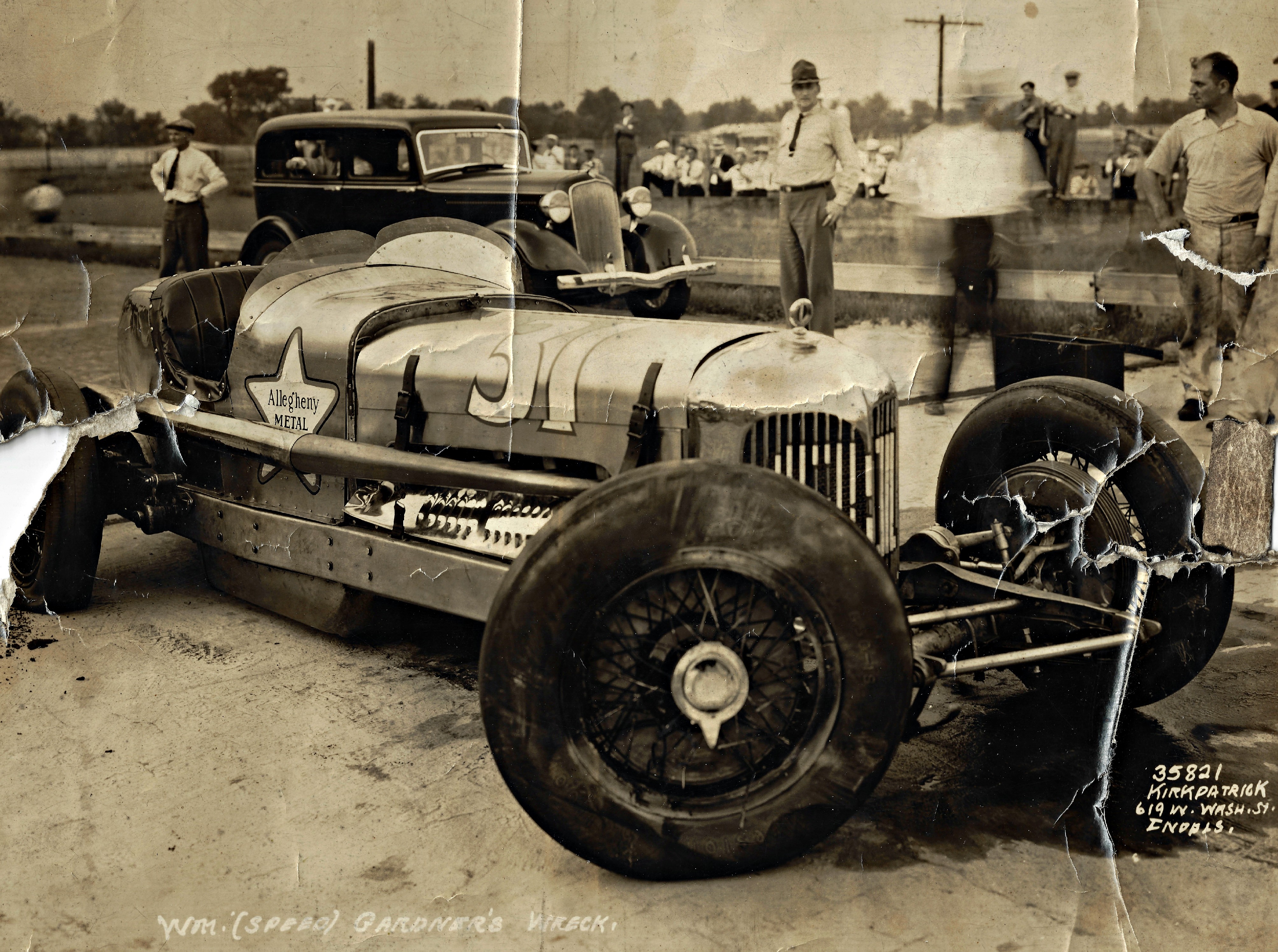

Undeterred, the team worked on their car in the off season and made another attempt using the Allegheny Metal Special in 1933. The entrants numbered 63, but unfortunately, in the qualifying race, Gardner wrecked the Special and the team failed to qualify. Steve Ference told his family that neither Cy nor Steve were happy with Gardner’s diving performance. Gardner blamed it on the machine. Gardner would leave the Mikan-Carson team and would not make another attempt together.

Undeterred, the team worked on their car in the off season and made another attempt using the Allegheny Metal Special in 1933. The entrants numbered 63, but unfortunately, in the qualifying race, Gardner wrecked the Special and the team failed to qualify. Steve Ference told his family that neither Cy nor Steve were happy with Gardner’s diving performance. Gardner blamed it on the machine. Gardner would leave the Mikan-Carson team and would not make another attempt together.

The Mikan-Carson team now needed a new plan. They would team with the Cresco Oil Company to build a new car and find a new driver. In 1934, Mikan-Carson teamed up with driver George "Doc" Mackenzie who ran in the previous two showings at Indy. Mackenzie was a bit of a showman and at one time vowed that he would not shave his beard until he finished tenth or better in the Indianapolis 500.

This new team found success and managed to qualify to run in the 22nd Annual Indianapolis 500. On May 30, 1934, the Cresco Special lined up in the ninth row (9 of 11). Unfortunately, in the 16th lap of the race, ‘Doc’ Mackenzie tried to squeeze his car past Gene Haustein’s Hudson and crashed over the cement safety wall of “coroner’s curve.” The car was unable to finish the race. The Mikan-Carson team placed 29 out of 33 that race day. Their take of the purse was $490. Mackenzie would not return to the team for the 1935 season. Instead, Mackenzie raced for a new team, and in 1935 place 9th overall. Mackenzie would then take 3rd place in the 1936 season at Indianapolis. Unfortunately, George "Doc" Mackenzie would lose his life at the age of 30 while running a race in Milwaukee later that year.

This new team found success and managed to qualify to run in the 22nd Annual Indianapolis 500. On May 30, 1934, the Cresco Special lined up in the ninth row (9 of 11). Unfortunately, in the 16th lap of the race, ‘Doc’ Mackenzie tried to squeeze his car past Gene Haustein’s Hudson and crashed over the cement safety wall of “coroner’s curve.” The car was unable to finish the race. The Mikan-Carson team placed 29 out of 33 that race day. Their take of the purse was $490. Mackenzie would not return to the team for the 1935 season. Instead, Mackenzie raced for a new team, and in 1935 place 9th overall. Mackenzie would then take 3rd place in the 1936 season at Indianapolis. Unfortunately, George "Doc" Mackenzie would lose his life at the age of 30 while running a race in Milwaukee later that year.

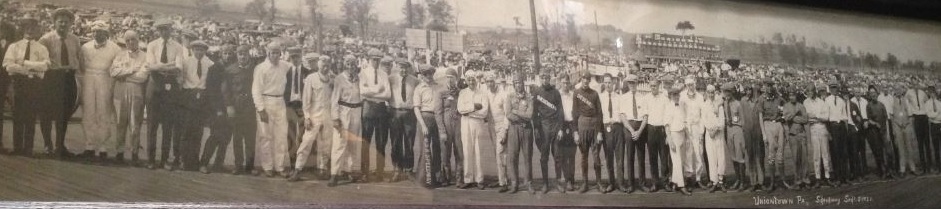

In 1935, the Mikan-Carson team would put a new driver behind the wheel of the Cresco Special. A twenty-six year old driver named Harris Insinger would start as a rookie driver in the “Decoration Day Race,” lining up in the eleventh row. Insinger gave the Mikan-Carson team their best showing to date, finishing the race in 14th place overall. While the first 12 cars ran all 200 laps, Insinger was able to complete at least 185 laps. The team from Trafford City not only collected it’s winning purse of $535, but they rubbed elbows with Eddie Rickenbacker, Harvey Firestone, and Amelia Earhart when they took the group photo shown below. Unfortunately, this joy would be short lived. Harris Insinger was killed in a crash just four months later while competing in a race at the Oakland Speedway in California. On September 8, 1935 the wheel of opposing driver Al Gordon’s car “hooked onto Insinger’s vehicle and carriage, like some stricken animal, rolled and rolled and finally stopped, and when they picked up Harris he was with a few minutes of being dead.”

In 1935, the Mikan-Carson team would put a new driver behind the wheel of the Cresco Special. A twenty-six year old driver named Harris Insinger would start as a rookie driver in the “Decoration Day Race,” lining up in the eleventh row. Insinger gave the Mikan-Carson team their best showing to date, finishing the race in 14th place overall. While the first 12 cars ran all 200 laps, Insinger was able to complete at least 185 laps. The team from Trafford City not only collected it’s winning purse of $535, but they rubbed elbows with Eddie Rickenbacker, Harvey Firestone, and Amelia Earhart when they took the group photo shown below. Unfortunately, this joy would be short lived. Harris Insinger was killed in a crash just four months later while competing in a race at the Oakland Speedway in California. On September 8, 1935 the wheel of opposing driver Al Gordon’s car “hooked onto Insinger’s vehicle and carriage, like some stricken animal, rolled and rolled and finally stopped, and when they picked up Harris he was with a few minutes of being dead.”

In 1936, Pittsburgh suffered the worst flood in its history when flood levels peaked at 46 feet. Reynold Peduzzi was one of the central figures in keeping KDKA on the air after the electric power failed. The Westinghouse Company tasked him with connecting a gasoline engine to a generator to create current for the failing batteries. National Guardsmen escorted Peduzzi through the flood stricken areas of Pittsburgh to ensure he was able to complete his work. Is it possible that the devastating damage to the city, coupled with the loss of life to the drivers close to this group of men caused the racing team to change course? The Mikan-Carson would not return a car to Indianapolis.

Cy Mikan spent his remaining time in Trafford focused on raising his family and building a successful automobile business. He passed away in 1968 at the age of 64. His young apprentice, Jack Carson, finished school and headed to work on the Panama Canal lock expansion project as an engineer. Jack Carson died in Huston, Texas in 1977 at the age of 64.

Photo credits: Dolores Bigler-Capets, Reynold Peduzzi Jr, Robert Mikan, The News-Herald (Franklin, Pennsylvania), Oakland Tribune (Oakland, California).

Click picture below to watch film of the 1935 Indy 500